Uncle Al and The Big Rock Candy Mountain

As I look back over the years—from childhood through adulthood—I can trace a trail of moments that quietly nurtured my interest in art. None of them ever struck me like lightning, made me pause and declare, “This is it. I’m going to take art seriously.” But each one added something to the atmosphere, like brushstrokes building a background. Art was always something I enjoyed, yet, it remained in the shadows, eclipsed by other pursuits. In today’s blog post, I’ll talk about one of those moments.

After my first turn-out, summer and fall riding experience, the years rolled by in a steady rhythm, marked by seasons and routines. Each summer, I returned to the mountain to help manage the association herd—living among the pines and sagebrush, working cattle under wide skies. Old Snap was gone, and I’d finally moved up to one of the regular saddle horses—a quiet milestone that marked my growing place in the herd and the work. When fall came and school was back in session, my weekends were spent cow-punching, especially during the big roundups. By late October, the cattle began drifting off the range, and by Thanksgiving, most ranchers’ corrals were full again.

Winter and spring brought a different kind of work. On weekends, I’d join Dad at the farm, feeding a diet of grain, corn silage, and hay to the steers penned in the corrals and tending to the mother cows and their calves out in the open fields. It was a rhythm I knew well—quiet, steady, and stitched into the fabric of my growing-up years.

As I grew older and gained more experience, my role with the cattle expanded—no longer just a drag rider trailing behind. The romantic notion of being a cowboy gradually gave way to a more practical truth: I was a ranch hand, doing whatever needed to be done to help the family farm succeed.

Eventually, I was old enough to drive the tractor during hay season. After our own crop was in, I even got hired by a neighbor to help with theirs. I was part of a paid crew, earning twenty-five cents an hour for several days. That was big-time money for me back then—and it felt like I was really stepping into the world of work.

My hometown was changing too—slowly but surely. The first televisions began to appear, and I remember our neighbor across the street getting one. Before long, TV antennas were popping up like weeds on rooftops all over town.

The following year, we got our own set. It was black and white, with a snowy picture and fuzzy sound—but we were hooked. We’d sit mesmerized, watching whatever came through the static. Just like that, the old ritual of gathering around the radio faded. No more Lone Ranger, Mr. and Mrs. North, or the radio version of Gunsmoke echoing through the living room. A new era had arrived, flickering to life on a glowing screen.

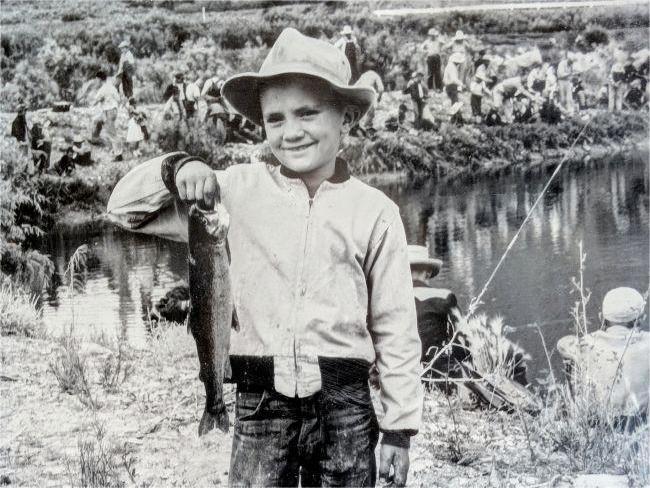

I had a buddy who lived just down the block—his name was Ted too. His dad worked for the post office, and the two of us were inseparable. We rode our bikes out to the hills south of town to fly kites, hunted jackrabbits in the same dusty stretches, and I often tagged along when his dad took us fishing. Fishing season always kicked off on the Saturday closest to June 1st, and by sixth grade, we saw an opportunity. We became young entrepreneurs, selling night crawlers to the local fishermen.

Back then, most families watered their lawns and gardens from the irrigation ditch. Once we figured out the watering schedule, we’d follow the ditch and hunt for crawlers on freshly soaked lawns. At first, we went together, but soon we split up—each taking our own route along different ditches.

Worm hunting was a swing-shift job, done after dark, which suited me just fine. I’d come off the mountain on Wednesday or Saturday afternoon, wait for nightfall, then head out on my bike with a flashlight and a coffee can. A full can held ten dozen crawlers—a solid haul at fifteen cents a dozen.

It usually took until midnight or one in the morning to finish, but no one worried. That was the difference between then and now—things felt safer.

The crawlers were stored in a box of peat moss shaded by the cellar. I’d head back to the mountain the next day, and Mom would handle the sales. We had regular customers, and if no one was home, they’d help themselves and leave the money in a can by the box. It was a simple system, built on trust—and it worked.

One year, a woman in town announced she’d be offering oil painting lessons for kids. I didn’t know much about painting with oils—what it involved or how it worked—but something about it caught my interest. My buddy Ted signed up right away. We couldn’t afford it, or at least that’s what my mother said.

Not long after, Ted came home proudly carrying his first finished piece. It was a covered wagon, painted with bold strokes and the frontier spirit of a twelve year old. I remember feeling a twinge of envy—not just for the painting, but for the chance to try something new, something creative. I suppose that was the first time I realized how much I wanted to be part of that world.

I must have let slip to my mother how disappointed I was about missing out, because—like good mothers often do—she took action. The very next day, she told me she’d gone down to talk with Uncle Al. I didn’t know whose uncle he was, but he certainly wasn’t mine. Turns out he was an old-timer who lived on State Street, and everyone in town just called him Uncle Al. Even better, he was an oil painter.

He must have seen something in me worth encouraging, because he offered to give me oil painting lessons—free of charge. I was thrilled. The very next day, I walked the few blocks to his house, nervous with anticipation. He welcomed me in, and just like that, the lessons began.

He had a small postcard image of The Big Rock Candy Mountain—a vivid cluster of hills just north of Marysvale, Utah, glowing with color along the banks of the Sevier River. That was our subject. With quiet patience, he guided me through the basics, suggesting brushes and colors, demonstrating techniques, then stepping back to let me stumble through my own strokes.

Over the course of several days, I managed to finish the painting. It wasn’t perfect—not by a long shot—but it was mine. I carried it home with quiet pride. Mother, of course, showed it off to anyone who came within arm’s reach. They all nodded, smiled, and told me how wonderful it was.

Years later, I looked at that painting again. They were lying.

Still, that small act of kindness from Uncle Al cracked something open—a door I hadn’t even known was there. Through it lay the world of art, and a part of myself I was just beginning to uncover.

Uncle Al had sent me home with a rudimentary paint set—some worn brushes and half-used tubes of oil paint. Armed with those and a newfound sense of expertise, I set out to create more. My first solo effort was a small painting of a rooster pheasant, which I proudly gave to my brother.

At his house, you could either head upstairs to the kitchen or downstairs to the basement. He hung my little pheasant painting on the wall just to the left of the three steps leading up to the kitchen and living room. I figured he must’ve liked it well enough—it stayed there for over fifty years

My next project was more ambitious—a larger canvas with mountains and pine trees rising in the background, a lake nestled mid-picture, and a grassy meadow stretching across the foreground. I even added a cow or two grazing peacefully in the field. It took me quite a while to finish.

Looking back, I’m fairly certain I copied the scene from a magazine or some printed image. But at twelve years old, I didn’t know a thing about artistic ethics or copyright. I just wanted to paint something beautiful—and that felt like enough.

One day, an uncle—my dad’s brother-in-law—came by for a visit. Naturally, my mother pulled out my latest painting to show off. He took one look and started raving about it, then asked how much I wanted for it.

I’d never even considered the idea that someone might want to buy my work. My confidence shot up like a rocket, but I had no clue what to charge. He offered me ten bucks, and I jumped at it.

In the years that followed, he never brought it up again. Maybe the painting didn’t hold up quite as well in the sober light of day—but for me, it was still a proud moment. My first sale, even if it came with a generous dose of enthusiasm and an inebriated uncle.

My mother, ever enthusiastic, had me painting in nearly every spare moment. I think she hoped I’d steer clear of the rough-and-tumble rancher path my dad and brothers had taken. It wasn’t my fault she didn’t get a daughter—but I could feel her nudging me toward something softer, something different.

After that, I think I only completed one more painting—a desert scene with towering saguaro cacti, though the details have mostly faded from memory. My enthusiasm for the hobby was beginning to slip away. Spending long hours indoors, alone with brushes and paint, started to feel stifling for a kid who preferred movement, sunlight, and the company of friends. The spark was dimming, and I could feel myself drifting back toward the rhythm of the outdoors.

Truth was, I missed my friends. I missed riding bikes and hanging out with my buddy Ted—who, by the way, never picked up a brush again after those first lessons.

One day, I simply announced I was done. I didn’t want to paint anymore. Didn’t want to be an artist. I suppose my mother was disappointed, but she never let it show. I packed away the paint set and didn’t think much about art again for years.

And that was fine. I was heading into junior high and high school, where a whole new world of social distractions waited to take the place of my short-lived artistic career. There would be other creative sparks down the road—moments that would nudge me back toward art—but they were still waiting in the wings.